Railway 200 invites us to reflect on the incredible impact stations have had on shaping the modern world. The introduction of the railway connected communities, powered industries, and even standardised time, but it is the stations themselves that hold the key to understanding how much more the railways have offered. At first glance, stations seem like mere stepping stones, enabling passengers to buy a ticket and catch a train. However, their story goes much deeper. Looking back over the past 200 years, you can find something richer and far-reaching in their legacy.

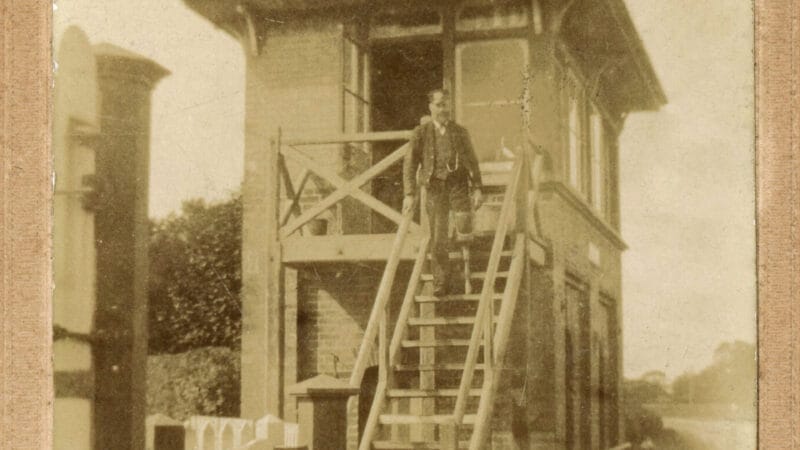

In the early days of rail travel, station design was not a priority. Perhaps unsurprisingly, many of the features found in the earliest railway stations were based on the transport mode they were to shortly usurp – the horse drawn coach. Passengers on the earliest railway services would not have even enjoyed the luxury of a platform, instead having to step up on to the waiting open top wagons where they would experience a journey that left many choking on the plumes of smoke exhaled by the leading locomotive. The opening of the Manchester to Liverpool Railway in 1830 marked not just the first intercity railway, but also what can be considered the first purpose-built railway stations. These stations were far from grand but offered something entirely new: ticket offices, waiting areas, and platforms that protected passengers from the elements. With the arrival of rail, towns quickly became more accessible, visible, and often more prosperous. Communities that had previously been isolated found themselves brought closer to the rest of the country and stations soon became a symbol of opportunity and growth.

The Victorian era saw railways spread across the country, accompanied by an ambitious programme of station construction. Grand stations, such as St Pancras and York, became symbols of civic pride. Simultaneously, smaller towns and villages gained locally significant stations, reflecting their regional identity. These stations were not merely functional; they were designed to complement the character of their communities. Stations brought jobs, business, and new trade opportunities. Hotels, cafés, and market stalls flourished, while new avenues for commuting, education, and leisure travel emerged. For many towns, the station was the gateway to the wider world, shaping the community’s identity.

Before television and the internet, railway stations were often the first place to hear the latest news, delivered by specialised postal cars on selected rail services. Families gathered to say goodbye or welcome home loved ones. Soldiers departed for war and returned to tearful reunions. The station became a central space for life’s most significant moments. Beyond transport, stations played a key role in shaping local identity. The architecture, the sounds of departing trains, and even the smell of coal became embedded in the rhythms of daily life. In this sense, stations transcended their functional role and became integral to the cultural fabric of their communities.

The 20th century brought both progress and challenges. The rise of cars, buses, and air travel led to a decline in rail travel, the Beeching Report (published in 1963) recommended closing thousands of miles of railway lines that were deemed ‘unprofitable’ as well as over 2,000 stations, with many of these being in rural or working-class areas. The closures were not only a loss of transport options but also led to a sense of disconnection for towns and villages that suddenly found themselves without railway links to the wider world. The closure of a station often symbolised the loss of status and opportunity. As a literary text, the Beeching Report’s pages of alphabetically ordered stations to be closed were scorned by contemporary media outlets as looking like names on a war memorial. This sombre list inspired an immediate Guardian editorial entitled ‘Lament’, which ended ‘Yorton, Wressle, and Gospel Oak, the richness of your heritage is ended. We shall not stop at you again; for Dr Beeching stops at nothing’. However, many communities resisted this decline. Some successfully campaigned to save their stations, while others repurposed disused buildings as libraries, community centres, and small businesses, maintaining their local significance.

In recent years, attitudes toward railway stations have shifted. With the growing awareness of climate change, congestion, and regional inequality, rail transport has re-emerged as a solution. Stations have once again become key community assets, with many once-neglected stations being revived and repurposed, with some transforming into heritage centres, co-working spaces, and cultural venues. Redevelopments like Birmingham New Street have turned stations into multi-functional hubs, while smaller stations, like those in Hebden Bridge, have made a significant impact on local communities and businesses that support the increasing leisure market. For people in rural or car-free areas, stations are a lifeline, providing essential connections. New stations in places like Cranbrook in Devon and Barking Riverside in London are unlocking opportunities for housing and economic growth. Stations also serve as interchanges for various transport modes, from buses and trams to bicycles, enhancing sustainable travel options.

Looking ahead, railway stations will remain central to Britain’s transport infrastructure. As the country moves forward with plans for high-speed rail, urban regeneration, and rural revival, stations must stay closely connected to the communities they serve. The best stations reflect local needs, promote social interaction, and foster civic pride. From local art exhibitions to community-run gardens on station platforms, the possibilities for stations to serve as both transport hubs and community spaces are endless. The railway station has been part of British life for nearly two centuries and their true value lies not just in the departure boards or ticket sales, but in how they have connected people, opened new possibilities, and kept our towns and cities moving.

Oliver Wheeler, Rail Delivery Group

Oliver Wheeler, Rail Delivery Group