For Disability History Month, Dr Mike Esbester, Senior Lecturer in History at the University of Portsmouth and co-lead of the Railway Work, Life & Death project, explores how people with disabilities have long worked on our railways.

In the UK, Disability History Month runs between November December annually – this year, between 20 November and 20 December. It’s an important way of highlighting the contributions and place of people with disabilities in our past, present and future. Given one of the key themes of Railway 200 is ‘celebrating railway people’, Disability History Month marks an ideal time to think about where we might be able to find disabled people on our railways in the past – as well as in the present.

Looking historically helps us see how people with disabilities have long had a place in and on Britain’s railways. However, it can be hard to find much about disabled people’s experiences of railway travel and railway work, particularly once you move out of living memory. This reflects the ways in which society in the past often marginalised people with disabilities – yet it is still possible to find out more. For example, some of Dr Oli Betts’ research, in his role the National Railway Museum’s Research Lead, has explored blind passengers’ experiences of railway travel in the early twentieth century (you can watch his talk here).

Take the case of John Gillespie. It’s hard to find out much about him – he seems to have been an ordinary man. He was born in Coatbridge, near Glasgow, in 1866. He appears in the Railway Work, Life & Death project as he had an accident at Broxburn, near Edinburgh, in 1909. He was employed by the North British Railway (NBR) as a pilotman – someone responsible for accompanying a locomotive crew along a particular section of track, particularly if they weren’t familiar with the route. At 4.45pm on 29 November 1909, he was helping to couple wagons when a wagon wheel ran over his foot. The investigation into the incident noted that he shouldn’t have been coupling wagons because he lost his right arm and a finger on his left hand in 1886. This seems to be the only surviving record of John’s disability – without this very passing reference, we would have no idea. Fortunately, he survived, and continued working for the NBR afterwards. His disability was clearly no barrier to railway employment.

Elsewhere in the Railway Work, Life & Death project database, we can see workers with a range of disabilities – like North Eastern Railway platelayer William Leek, who was said to be deaf and involved in an accident at Bolton Percy, Yorkshire, in 1859. Staff with sight loss and other disabilities are also found in the records. So, we can see how employees with disabilities had a place in the railway industry.

As we know from our project’s research, railway work in the past was dangerous and sometimes caused disabilities. When that happened, some companies like the Great Western Railway, London and North Western Railway and North Eastern Railway used their workshops to manufacture prostheses for injured staff. There’s more on this in these blog posts from the Railway Work, Life & Death project.

Railway companies would often find a new role for the newly disabled worker. Demonstrating once again that physical disability did not reduce someone’s ability to work for the railways was Thomas Manners. Born in 1866, by the late 1890s he was working for the Barry Railway in south Wales as a brakesman – someone responsible for applying brakes on goods wagons. Unfortunately, he had an accident at Barry No. 2 Dock in March 1905, in which he lost his left leg. After the accident, Thomas made an active choice to stay with the Barry Railway, initially working in the dock telephone office. From there he worked his way up, to become the controller of Barry Docks in the 1920s, something we explore in this publication.

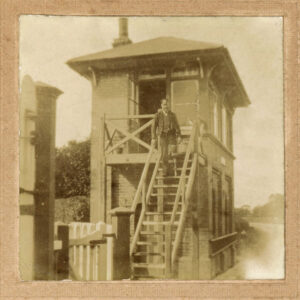

Similarly, shunter Walter Bridger had an accident at Three Bridges, Sussex, in 1873 in which he lost a leg. He returned to the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway, eventually becoming a signalman at Fishbourne, on the south coast of England. His was a life story the Portsmouth Area Railway Pasts project explored, with the help of Walter’s descendants. You can read more about Walter here.

Following up on often relatively small references in the documentary record allows us to see some of the rich variety of experience of disabled railway workers in the past. Importantly, that helps us to better appreciate and recognise the contributions that people with disabilities have made to our railway system since its earliest days.

As attitudes to and understanding of disabilities have changed over the last 200 years, so steps towards greater inclusivity have been taken. Appreciation of the importance of equity is now leading to much more active attempts to better represent the UK’s diversity in the make-up of staff in the rail industry and its customers. That includes through groups like Network Rail’s CanDo, an employee-run network for colleagues with disabilities and the Built Environment Accessibility Panel (BEAP), a voluntary panel providing expert advice about making built environments accessible

Whilst there’s still more to do, progress has been made in terms of making our railways more accessible, for staff, passengers and all who encounter and use the system. Looking historically helps us see where the industry and wider society has come from. It also shows us how the industry has included people with disabilities in the past and reminds us of the importance of continuing to strive for improvements.